Imagine: There is a recognized public health crisis, with disparate impacts on minority communities.

Two Pittsburgh-area organizations recognize their potential role in addressing the crisis.

Both organizations realize they need a partner.

These factors came together in 1968. The result: a revolution in emergency medicine led by a civil rights organization based in the Hill District and pioneers in life-saving techniques in Oakland. But these factors are coming together again over 55 years later. This time, the crisis is in youth mental health. And once again, successor agencies to those that collaborated in the 1960’s are seeking the same successes in mental health access and outcomes as were achieved by Freedom House Ambulance Service and Presbyterian University Hospital in emergency medicine.

By the 1960’s most cities had well-developed services for community needs: police, fire, sanitation. But, although military ambulance corps had been effective in wartime as early as World War I, civilian emergency medicine only existed in hospitals. People with urgent illnesses like heart attacks or injuries from accidents received no medical care when they called for help. They just received transportation from untrained services like police, firefighters, often even undertakers. According to John Moon, a Hill District resident of the time, “you’d call the police and they’d pick you up, throw you in the back of a paddywagon, and rush you off to the hospital. And on top of that, both officers got up front.” At best, patients received very basic first aid, an oxygen tank, and a pillow. Left to fend for themselves in the back of the police van, there was no one there to assist the injured or ill patient.

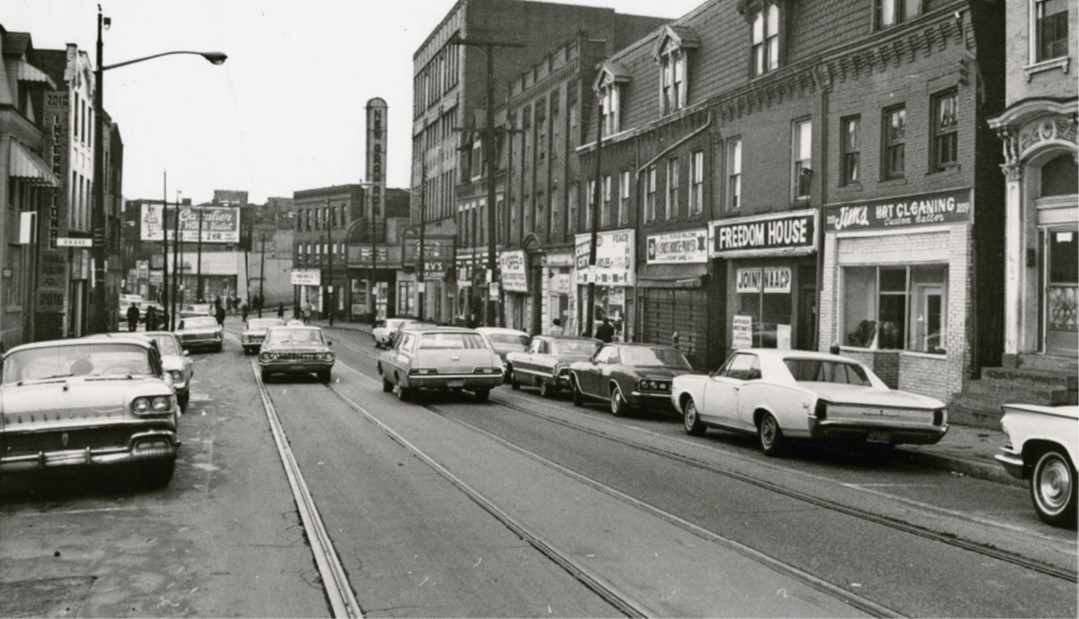

This practice of “swoop and scoop” became even more ineffective in underserved minority neighborhoods. By 1967, in the wake of civil unrest and an entrenched Jim Crow culture, sick or injured people in neighborhoods like the Hill District could not even reliably depend on this minimal level of transportation. “Pittsburgh’s mostly white police force was often slow to respond to emergencies in the Hill, while many Black residents were reluctant to even call the police to begin with.”

Given this situation, civil rights leaders in the Hill recognized that city services were not going to fix the problem. James McCoy Jr. was the founder of Freedom House Enterprises (FHE), an agency that grew out of a protest wing of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and helped find jobs, organize voter registration, and support civil rights activities in the Hill District. McCoy and others recognized that a fleet of trucks and an organized distribution system, developed at Freedom House to offer food delivery, provided the infrastructure necessary to create a community ambulance service. However, such a project lacked funding and, more importantly, medical expertise.

By this time, the lack of adequate emergency services was a well-recognized national problem. A federal study in 1966 identified as many as 50,000 deaths per year that were occurring due to a lack of pre-hospital care. The “White Paper,” as it came to be known, motivated significant federal spending for emergency care, but localities did not initially know how to use the funds. In Pittsburgh, Philip Hallen was director of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, which was focusing on the growing public health crisis in Black communities. The Falk Fund had money, Freedom House had trucks and organization, but Hallen also had a connection for the final missing piece.

Hallen reached out to Dr. Peter Safar, then head of anesthesiology at Presbyterian University Hospital (PUH), who was a pioneer in CPR development. Dr. Safar already had a vision for emergency medical care provided in the field via trained technicians giving treatment and transportation at the same time, as military ambulances had in Korea and Vietnam. The key to his vision was to train ordinary citizens—non-medical personnel—in emergency treatments like CPR.

This fit perfectly within the scope of Freedom House’s job creation services, and with support from the Falk Fund and Dr. Safar’s medical team, the project took off. After witnessing some of the first class of Freedom House EMTs in action from his job as an orderly at PUH, John Moon joined the corps a few years later, mastering advanced techniques with his colleagues and becoming one of Freedom House’s most experienced paramedics.

In its first year of operation, Freedom House saved more than 200 lives. The service quickly grew, making up to 6,000 emergency calls annually, and changing emergency medical care locally, nationally, and internationally.

.jpg)

Fast-forward 55 years. In the wake of the COVID pandemic, civil upheaval including wars and political unrest, and the increasing reality of climate change, providers and researchers around the world recognize an explosive increase in mental health challenges among youth. “The statistics paint a bleak picture: a significant rise in cases of depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders among teenagers over the last decade [2014-2024]. According to the American Psychological Association, the rate of those experiencing depressive episodes has risen exponentially.”

As with the crisis in emergency medical care in the 1960’s, this problem is measurably worse in minority communities. Not only are rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, substance use disorders and suicide rising more quickly among racial and ethnic minorities, but availability of care to these youth is worse than among their white peers.

- High-quality, evidence-based care is less commonly provided to racial and ethnicity minority [sic] compared to White children for several common mental and behavioral health (MBH) conditions including anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance use. Children whose MBH conditions remain inadequately treated in the outpatient setting may be at greater risk of developing a MBH crisis. From 2011 to 2016, ED visits for MBH conditions increased at faster rates for Black and Hispanic children than White children.

-

Hoffmann, J. A., Alegría, M., Alvarez, K., Anosike, A., Shah, P. P., Simon, K. M., & Lee, L. K. (2022). Disparities in Pediatric Mental and Behavioral Health Conditions. Pediatrics, 150(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-058227

Enter the successor organizations to Freedom House and Presbyterian University Hospital. Freedom House had been an off-shoot of NAACP of Pittsburgh in the 1960’s; “Presby” is now part of UPMC. Responding to the emerging crisis in youth mental health care and disparities in care in minority communities, NAACP of Pittsburgh and the UPMC Theiss Center for Child and Adolescent Trauma are coming together to tackle the current public health emergency in the spirit of Freedom House Ambulance Service.

Efforts of this collaboration, called “Together We Rise, Together We Thrive,” begin with a 21st century approach to providing access to established mental health services for youth who may not know where to turn or even what they are experiencing. Through this website and connected community outreach, the first step is to use this collaboration between UPMC and NAACP to build trust in the community. Key to this will be providing information and resources to youth and parents alike. As noted by Kevin Mosley, chair of the NAACP’s Health Committee and co-founder of the Together We Rise collaboration, “If parents understand it, it may increase the children understanding it too.” The ultimate goal: reduce (or even eliminate) disparities that exist now for communities of color in mental health and related services.